|

|

|

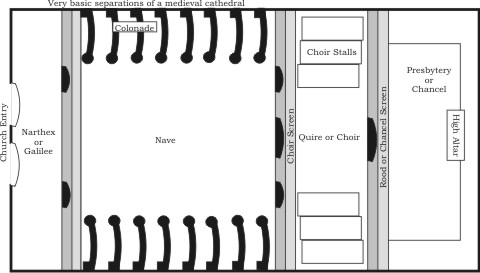

The Nave

Early

Christian churches emphasized the importance of the communal gathering

and there were few

screens, canopies, or curtains separating worshippers

from another, or clergy from the congregation, or the congregation from

the 'mysteries.' Walls and screens came in slowly, starting with

a wall beween the choir and the congregation. By the latter

middle ages, the great monastic

churches and cathedrals had separated the belly of the church into

distinct

sections, with walls or screens at the narthex, choir, and presbytery

(chancel). The goal at the time was to place primary importance

on the most sacred part of the church, that of the high altar, where

priests celebrated the Mass and Eucharist.

|

|

|

|

| The Nave

today is usually

the largest part of the church, the place where the general

congregation

assembles for worship. In the middle

ages, however, it was not necessarily largest and could be quite

small. Additionally, the medieval nave did not include

benches or chairs for seating: the congregation stood. The only

seating provided were stone benches built into the church walls where

the elderly, sick, or disabled could rest. |

|

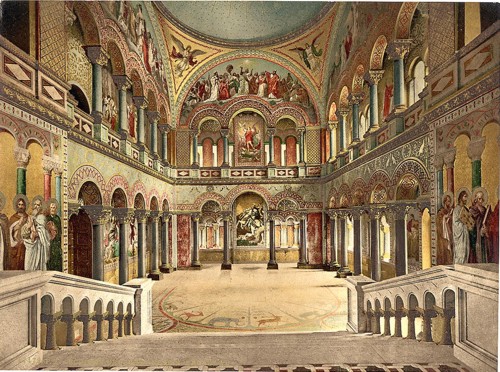

[Interior of St. John and St. Paul's, Venice, Italy] |

|

|

Churches of the

middle ages were

laid out in the form of the cross, with the top of that cross being

the

easternmost point. The parts of the church grew progressively more

sacred the

more easterly they were, so that while lowly penitents might enter the

Narthex

or

In some ways the configuration of the medieval churches imitate that of the 'great halls' built by the Kings of the West. In his palace or citadel, the medieval king would sit atop a throne on a raised daia at the top of an ornate and open hall. No one else in the hall would be allowed to sit, though they might lie prostrate on the floor. The great halls provided a physical demonstration of king's power and position (often further decorated with religious symbols). Only the chosen few, close aides, esteemed allies or officers, were allowed access to him and the dais. All other petitioners must keep their place or grovel at the door. |

|

[Throne room,

Neuschwanstein Castle, Upper Bavaria, Germany]

|

|

| While the ideals

of the church

communities differed from those of governing kings, some of the

trappings that

denoted power were similar for the church as for the hall.

Most particularly the use of penitential

entries, halls (naves), raised dais as inner sanctum (high altar), and

thrones. Like a king, the Abbot or Bishop,

as the tititular head

of that church, diocese, or see, would sit at the top, eastern part of

the

church in large, ornate thrones during the Divine Offices,

feasts and

during The Nave itself (or Navis, the Latin word for ship), was the central area of the church and in general use by the congregation. The area of the Nave included all the lateral space after the Narthex to the Choir Screen, including to the north and south of any supporting (or decorative) columns, arches or other architecture. Church activities in this space included guild plays (religious in nature) and fundraisers, just as today. In the middle ages, fund raising included a occasion to celebrate, such as a wedding or successful lambing season, and the distribution of plenty of good ale.  |

|

| Copyright (c) Richenda Fairhurst and historyfish.net, 2007 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. Keep author, source and copyright permissions with this article. | |