|

Property Rights and 'Copyright Forever'

by Richenda

Fairhurst March

2006

Copyrights and Property Rights are

not the same, but both property law

and copyright law restrict and protect the use and sale of artistic

works. Copyright protects the fixed expression of an idea.

Property rights protect the physical result of that expression. Copyrights and Property Rights are

not the same, but both property law

and copyright law restrict and protect the use and sale of artistic

works. Copyright protects the fixed expression of an idea.

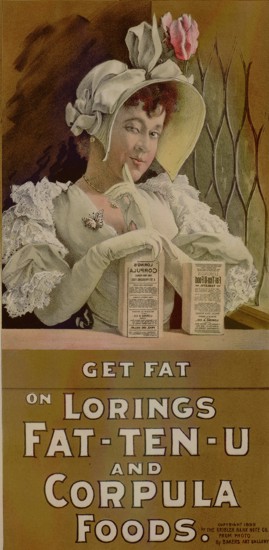

Property rights protect the physical result of that expression.Think of ‘expression’ and ‘medium’ as two separate aspects of the same artwork. The ‘expression’ of a photograph is the image itself. This part, in color or black and white, depicts something: a building, children playing, a train, anything. The second aspect, the ‘medium,’ of a photograph, is the photographic paper, the ink, the gloss, all the material stuff you can hold in your hand. In a nutshell, copyright laws protect fixed ‘expression.’ So the image, that one-of-a-kind depiction of that building or those children playing, that is the part protected by copyright. 'Expression' is an abstract concept. You cannot hold it in your hand, you need ink or paint or clay. Expression is basically an idea. But become "fixed," that idea has to be made into a form that can be physically experienced by others. Let’s say a photographer imagines a scene in his mind. The scene he imagines is of two small children playing at the beach. He imagines their surprise, then glee, as the ball they are playing with rolls into the water and splashes back onto the beach. This is his idea for a photograph, but as yet the idea exists only in his mind. The photographer then goes to the beach. He sees two children playing, offers them a ball and then sits back, camera at the ready. He chooses just the right moment to take the photograph. When the photograph is developed, the idea in his mind has now taken a “fixed” form. It is now an image, a fixed, creative “expression” and protected by copyright. The image of the beach nowexists as a photographic image. Yet the photograph is only one way the photographer can display the image. He could choose to display the image in other ways, too. The photographer could paint that same image in watercolor as a painting, or he could draw the same image in chalk on the sidewalk. That fixed image still belongs to him. The image, but not the chalk. He could use his children’s chalk if he wanted. The image would still be his even if the chalk was not. Likewise, the photographer does not own the sidewalk. He cannot pick up the chalk or the sidewalk and take the image home. But that part of it that is the image, it, as expression, is his ‘Intellectual Property.’ He owns all the rights to it--in chalk or in paint or as a photograph--and he alone has the right to copy, reproduce, or profit from it. This is copyright. Property rights are different. Let’s say the photographer makes 100 postcards of the image. The postcards sell well, and now 100 people own a postcard, and so there are now 100 copies of the image. A tall woman purchases one of the postcards, this postcard is now her property. The tall woman is now the owner of the postcard. She bought it because she liked the image. And she can now shred her postcard, mail it, or stick it in the window of her car. The postcard belongs to her. Even the ink belongs to her. But the image, the ‘fixed expression’ of the two children on the beach, does not. Back to the chalk and the sidewalk. The photographer owned the image, the children owned the chalk, and the city owned the sidewalk. The tall woman owns the ink and the postcard, but she does not own copyright to the image. The photographer owns the copyright. The tall woman cannot make copies of the image to sell because the image does not belong to her. She cannot make copies for her friends, or scan the image and post it on myspace. If she want more copies of the image to give as gifts, she has to go to the photographer and ask for them. She needs his permission. The rules change once an image becomes part of the Public Domain. The image and the material are still separate. But once an image is in the public domain, the image part no longer belongs exclusively to the artist. Anyone who wants to can now make copies of the image of the two children at the beach. They can paint the image on their cars, sell copies of the image in a gift store, or post copies of the image to the web. The postcard owner does not now own the image, but now that copyright has expired, that image it is in the public domain. The tall woman now has the right to use the image, make copies and sell them, as she wants. Property law becomes more important once copyrights have expired. Where before, the copyright owner had the right to say whether or not someone could make a copy of the image, now the property owner has a right to say whether or not someone can use their property--that postcard again--to get a copy of the image. Things have changed. Let’s say your grandmother is the little girl in that beach photograph. The photograph was taken in 1915, and you know the image is now in the public domain. But the only person with a copy of the postcard is your grouchy uncle Fred. Uncle Fred never liked you or your grandmother. When you ask for the postcard, he looks you in the eye, starts up the paper shredder, and shreds the blazes out of it. Can he do that? Yes. Because that particular copy of the image belonged to him. He does not have to share the image with you just because the image is in the public domain. And he can shred anything that belongs to him if he wants. It does not matter that it’s your grandmother in the picture. After all, being a jerk is legal. Some companies, libraries, and museums, our greatest and most valuable archivers, use property law to control the use of old images. They need to keep their doors open and money flowing in. Uncle Fred, it turns out, did not shred the last remaining copy of the photograph. The local museum has a copy, too. So you go to them and ask them for a copy of the image. They can say no. Or it might cost you. And even if you pay, the museum may still want to restricted how that photograph can be used. Now property laws, not copyright laws, are used to restrict use of the image. Copyright laws expire because, as a culture, we have determined that the free exchange of ideas and information benefits the culture more than the restriction of ideas and information. Some museums gripe about the restrictions imposed on them by copyright holders, yet ironically, some of these same museums restrict important works within their own collections by use of property rights. Property law can be more effective than copyright law when it comes to limiting public access and making a buck. While important archival libraries are supported this way, from the researcher’s end, things look pretty much the same: you have to pay, and you do not have any rights. Uncle Fred can make a fiery bonfire from the photographs in the basement and roast marshmallows in the flames. That may not be wise, but it is legal. His property rights supercede the rights of the public to the image, public domain or no. Uncle Fred can also refuse to sell the postcard for less than a million dollars. But can Uncle Fred make a copy, give it to you, charge you $50, and then tell you what you can and cannot do with what is now your copy of a public domain image? That is an interesting question. Personally, I worry that property rights are used as if they were an extension of copyright. The photographer who took the photograph is empowered to determine what may or may not happen to the image because he is entitled to benefit from his labor. But Uncle Fred did not create the image. He can give you access to his property or not as he pleases. Yet it seems to me that he should not have the right to dictate what you may or may not do with the image once you have a copy. If he does have that right, are we not then essentially granting copyright type protections to Uncle Fred (or institutions and businesses) into perpetuity? Is 'copyright forever' the intent of property law? Artists often donate their works to museums so they will be preserved for future generations. Additionally, many of these images are regionally, socially and historically valuable. They are our shared history. Occasionally, it can feel as if history is being held for ransom. Say you want to publish your grandmother’s photograph in The Atlantic Monthly with a story you wrote about her life. Too bad for you. Uncle Fred is controlling the access now. ********** This essay explores the difference between copyright and property rights using a hypothetical image. Just because an image is old, does not mean that image is in the public domain. Always check for permissions. More on “new” copyrights for “old images” here. Respond to this essay! Concerns? Corrections? Let me know what you think.  Important! This is a very general exploration of the difference between property law and copyright law, and is opinion only. This is not advice, only discussion. For real advice and information, see an intellectual rights attorney. Or see the US copyright office, I have also posted some helpful links for copyright research here. ********** Back to historyfish articles Go to historyfish.net |

| (c) Copyright Richenda

Fairhurst and historyfish.net, 2006 All rights reserved. No commercial permissions are granted. Permission freely granted to educators to copy and/or circulate this essay as needed for classroom use. Please keep author, source and copyright permissions with this article. Webmasters, feel free to link directly to this page. Disclaimer: Historyfish intends to generate discussion through community boards, essays, and shared information and does not claim to provide, in any way, formal, legal, or factual advice or information. These pages are opinion only. Opinions shared on historyfish are intended to be part of a wider discourse, and are not necessarily the opinions of historyfish editors, staff, or administration. Always consult proper authorities with questions pertaining to copyrights, property rights, and intellectual property rights. |